Big Easy bound: Cox embarks on New Orleans adventure

-

"This has been a great training ground," says architect and former Charlottesville Mayor Maurice Cox of his efforts in Charlottesville.Courteney Stuart

"This has been a great training ground," says architect and former Charlottesville Mayor Maurice Cox of his efforts in Charlottesville.Courteney Stuart -

Cox championed high-density in-fill development such as Waterhouse.hawes spencer

Cox championed high-density in-fill development such as Waterhouse.hawes spencer -

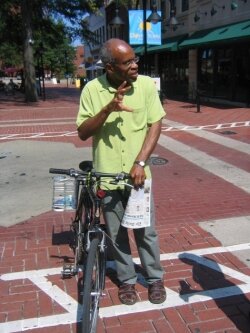

His own commuting habits, seen here in 2005, helped spur bike lanes.hawes spencer

His own commuting habits, seen here in 2005, helped spur bike lanes.hawes spencer

It's not the first time moving trucks have pulled away from the home of architecture professor and former Charlottesville Mayor Maurice Cox on Ridge Street. But this time, there's no planned return for the man perhaps best known for his support of high density urban development and alternative transportation– including his own early example of bicycle-commuting long before Charlottesville had bike lanes.

Cox is bound for New Orleans, where he's been named associate dean of community engagement at the Tulane University School of Architecture and will also serve as director of the Tulane City Center, the university's venue for collaborating with citizens and city leaders on the reconstruction of New Orleans.

"It's a tremendous opportunity," says Cox, who first got a glimpse of post-Katrina New Orleans as one of two design-skilled mayors called in to consult in the immediate aftermath of the 2005 hurricane. That was the year he returned from a one-year fellowship at Harvard University and two years before he'd take a three-year position with the National Endowment for the Arts in Washington, D.C.. Unlike those professional forays, the New Orleans gig is a permanent position, and an opportunity Cox says he couldn't turn down.

When the levees protecting that Louisiana city from flood water failed, epic destruction followed, and horrific scenes of death and racial disparity were broadcast around the world. But in the aftermath of the tragedy, Cox says, a rare opportunity arose, and city leaders embraced the challenge of rebuilding.

"It's taken a very long time, but they seem on the verge of making things happen," says Cox, who calls present day New Orleans "a hotbed of innovators."

Cox's experience as a civil servant coupled with his reputation as an advocate of outside-the-box urban development seems to have won him the job. It didn't hurt that the Tulane Architecture School Dean worked with Cox at UVA.

In a press release announcing the high-profile hire, Tulane Dean Kenneth Schwartz praises Cox as "unique among architectural educators" for his "ability to incorporate active citizen participation into the design process while achieving the highest quality of design excellence."

It's something Cox says he worked to do here in Charlottesville, where he was a city councilor from 1996 to 2004, serving as mayor the final two years.

The year he was elected, Cox says, the hottest topic was "reversion"– the idea that Charlottesville would give up its city status and become a town within Albemarle County, governed by county laws. Cox was opposed, he says, because he felt it would encourage sprawl into the urban ring rather than his favored growth approach of high density development within city limits. Eventually, his view prevailed, and he says the sight of multi-story buildings including the Holsinger and Waterhouse, both on Water Street, thrills him.

"Every time I look at a building over three stories in this town, I smile," says Cox. "I know that was a concerted push that inched our way up to higher density."

While the bike-riding mayor opposed the construction of the Meadowcreek Parkway, he says he's proud of the road's final design as a slim two-laner rather than a four-lane divided highway.

"The political reality was such that I never had the votes to kill it," says Cox. "It forced me to work with a whole lot of people to improve it."

With the city's portion of the parkway still unbuilt, the former mayor cautions today's leaders to remain vigilant over the project, particularly the road's 250/McIntire interchange.

"You look at it today, it's gotten inflated, bigger, and uglier," he says of the intersection that will connect the Parkway to downtown. "I'd argue that political leadership has taken its eye off the ball."

If his influence can be seen on projects including the Parkway and the redesign of the plaza at the east end of the Mall, which includes the modern Charlottesville Transit Center, as well as bike paths on nearly every major city thoroughfare, there's one project Cox says he wishes would have come to fruition.

"There's no question that I was hoping that Charlottesville would be the smallest American city with a streetcar system in place," says Cox, describing his vision of a public transportation system that would connect the transit center to the university campus to the Barracks Road Shopping Center.

"That would have fueled urban development for the next 20 years, and I believe it was genuinely possible," he says, bemoaning the fact that after his departure from council in 2004, the idea fizzled. "The lesson I learned is it's really hard to bring about changes as a private citizen," he says. "The moment you don't have the authority, you're just like everyone else who patiently waits for the city to take visionary acts."

While he's excited about the New Orleans adventure, Cox says leaving Charlottesville isn't easy– particularly the feeling of a small town, where, it seems, everyone knows his name.

As if on cue, a passerby shouts a greeting to Cox, who's sitting for an interview at a Downtown Mall cafe.

"The Honorable Maurice Cox," the man yells with a smile, as Cox smiles and returns the wave and greeting by name.

"Once a mayor, always a mayor here," he says, shaking his head. "I'm going to miss that."

But there's plenty to look forward to– in addition to the Big Easy's famed music and food.

"New Orleans is a much harder city, in terms of intensity and magnitude of problems," he says. "I'm hopeful I can bring a little bit of my optimism and belief that you can solve any problem."

***

Cox left Charlottesville on Thursday, August 2.

4 comments

Best of luck to him. I met him once and he was a really nice guy.

" While he's excited about the New Orleans adventure, Cox says leaving Charlottesville isn't easy– particularly the feeling of a small town, " but how will the higher density that Cox and others support allow for the feeling of a small town. Many of us wonder ?

Once the mountain views are blocked by buildings, and the sky begins to vanish, that is when I will look for greener pastures. Mr. Cox and other urbanists may find the flight out of the urban core, with it's urban problems encouraging city dwellers to head for the hills

It never ceases to amaze me how journalists love to insert volatile yet undocumented little "firebrand tidbits" into articles to, I suppose, add "color." Example: "...scenes of death and destruction and images of racial disparity." A completely loaded term without editorial balance by the writer. Perhaps, if she was going to insert that charged line in the article, she should have also cited statistics (as I am sure any good academic like Mr. Cox would desire):

New Orleans--28% white population; 37% of fatalities were white

67% black population; 59% of deaths were black

4% of population is other; 5% of deaths were other

Courteney, you could have done without that trite Spike Lee-type tripe.

R.I.P.: Barry Cowsill

"There's no question that I was hoping that Charlottesville would be the smallest American city with a streetcar system in place," says Cox, describing his vision of a public transportation system that would connect the transit center to the university campus to the Barracks Road Shopping Center.

We have transit from the downtown station, through UVA to Barracks RD and even to Fashion Square. It's called Route 7.

One day recently, traffic on W. Main was blocked and Route 7 was merely re-routed. An electric car would have had to stop running. A street cars inflexibility of route is the reason why we do not have one now. That makes the bus a mode of transportation superior to that provided by a streetcar. Bux breaks down? Substitute in another. There are no backup street cars sitting around because of the expense.